First published with Cha: An Asian Literary Journal, 23 Nov., 2023.

Translation is currently being discussed across academic disciplines and recognised as an essential process, performance, and metaphor for 21st-century realities as we engage with people and products from across the globe on a daily basis. My morning coffee has been through several translations: from the literal translation of information on the packaging to the cultural translation of a 15th-century Sufi aid to concentration into an integral part of waking workday rituals across the planet. Finally, it involves a metaphoric translation of substance into sensation, of hot black liquid into a sense of wellbeing and alertness. But such processes are not necessarily benign, and in the moment of coffee-fuelled bliss, the modern slavery taking place on many non-Fairtrade plantations gets lost in translation.

Translation is rarely a simple equal exchange but mostly constitutes, as Yunte Huang and Hangping Xu rightly point out in their introduction to the latest issue of Prism, “a multidirectional and intertextual hermeneutic process” (3). This special issue on Translatability and Transmediality: Chinese Poetry in/and the World “troubles the power asymmetry between national and world literatures, or between the Wets and the Rest [by investigating] how Chinese poetry interacts with the world via the criss-crossing routes of translation, dissemination, diaspora, mediation, transmission, reception, reincarnation, return, and so on” (2). It aims to investigate poetic translation from the perspective of a “a polycentric world” (4) and presents a bouquet of 12 diverse chapters on the subject. As such, it forms a rich source of inspiration for both translation scholars, poetry scholars, and all researchers interested in experimental modes of literary comparison. I opened the volume to feed my increasing interest in literary translation and came out more curious than ever and with a new craving for poetry.

I really enjoyed Shengwing Wu’s piece on how modernist poets used classical poetic motifs like wang 望 (looking into the distance) to describe modern technology like the Eiffel Tower or gazing at the moon through a telescope: “playing skilfully with the literal and figurative meanings or words (Buddhist or other culturally loaded terms) and engaging in extensive corporation with tradition and imaginative mediation, these poets also translated their sensory perceptions and emotions, in somewhat different manners, into the classical-style forms” (37). Translating extremely contemporary hi-tech inventions into the language of a poetic past creates a delightful twist that shows just how much translation (between languages, periods, or cultures) adds to a text. Cosima Bruno and Lianjun Yan in their essay likewise highlight poems inspired by poems, and propose to view such instances not as two units in an intertextual comparison, but as entangled poetry with translation as “a medium, an origin, and an afterlife” (171).

While surprising new context can have an artistic effect, Haun Saussy, in his analysis, shows how the extreme decontextualisation of anthologies misrepresents and risks mistranslating poetry. Examples he gives include a series of poems by Wang Wei that were originally published as a poetic conversation with Pei Di and which have since entered world literature as what he calls “pure poems”. Saussy argues that rather than freeing the individual poem, such radical decontextualisation risks freezing it into a synecdoche for an entire nation’s poetry. He concludes that “[c]areful attention to poems and paintings—outside the constricting frames of anthologisation and museum display—reveals their internal multiplicity and provides one form of resistance to the binding force of nationally ordained cosmologies” (22).

In her elegant expose of the immense Russian influence on modern Chinese poetry, Michelle Yeh shows just how little sense such bordered in versions of national poetry make, while Hangping Xu experiments with the notion of “translation as an interpretive performance, positing a translator’s relationship to the source text as akin to an actor’s relationship to their script” (228), proposing that the translator incorporate not only content but also context into their performance.

Through the new contexts and new performances that translation introduces, whole new genres of poetry may arise. Xiaorong Li demonstrates how poems translated by New Style sensual-sentimental xiangyan 香艷 poets “not only attempted to seek a common ground among different cultural expressions but also allowed themselves to be inspired by the source texts and create something hitherto unseen in the target language and culture” (72) such as using wen 吻 as a term for romantic kissing. Nick Admussen suggests that such processes of enrichment and innovation might be beneficial in academia as well as poetry. He explores a current rise of scholar-poets in US universities and argues that the interdisciplinary translation of scholarship into poetry might help admit and acknowledge the personal in the academic—the individual circumstances and accidents that affects what and how we study.

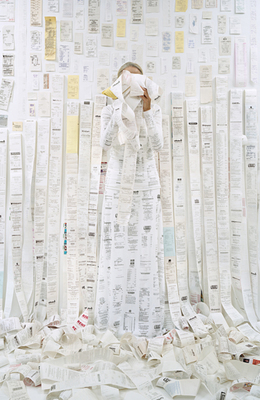

Several of the essays in the special issue deal with the politics of translation, such as Maghiel van Crevel, who analyses contemporary battler poetry (打工诗歌) “written on the flip-side of the MADE IN CHINA label” (203). He criticises the fact that “it is especially in translation that a single author can come to operate as a synecdoche for an entire literary genre” (206) and proposes the term hypertranslatable for a text that “elicits especially high numbers of translations, whose perspectives on the source text and its reproduction may converge but may also differ widely and indeed irreconcilably” (209). Adding a historical dimension to the discussion of the politics of cultural exchange, Chris Song examines the case of Dong Xun and Thomas Francis Wade’s collaborative translation of Longfellow’s “Psalm of Life” as an instance of diplomacy through poetry with translation as a prime mechanism of early soft power exchanges. Coinciding with Wade’s appointment as chargé d’affaires, the “poetry translation at the time was part of the means to incorporate social activities and cultural exchanges into his diplomatic practice that aimed to exert ‘pressure of inconvenience without hostility’” (80).

Lucas Klein sees translation as an extension of the poem and proposes that the poetics of translation is always political. Inspired by his works on poems from the Angel Island detention center, he writes that “rather than thinking in terms of foreignisation and nativisation, I ask if some translations assimilate their source texts, while other lock their source texts in detention” (101). If a translation locks its poem in detention by being too focused on the politics of content and context, “assimilated translation demands too little room for itself, challenges too little” (101). Klein proposes that multiple translations and translations that pay attention to the political in the aesthetic may be just as relevant and even more powerful.

Rather than an extension of something that is already there, Jacob Edmond seeks to invert our view of translation and invites readers to reimagine their internal literary world maps so that the intercultural, intertextual seas take centre stage and national literatures recede to appear as accidental nodules in a vast ocean of translation. As he posits, translation is “not as something that happens to national literatures but as what constitutes them” (139). Inspired by Bei Dao’s understanding of creative writing as a form of translation whereby a writer translates their thoughts, sensations, and experiences into words, he purports that “translation is not just something that happens to the already fully formed literary work but is frequently interwoven into the fabric of its making” (154).

Read together, this volume is a multifaceted and polyvocal intervention in the current discussion of how thinking in and through translation can help scholars/poets/humans rethink and challenge uneven power relations and understand the complexities and entanglements of contemporary literature in ways that go beyond national canons or elitist world literature anthologies to embrace the creative mess of literary entanglement across space, time, and languages. I wholeheartedly agree with Edmond when he echoes Epeli Hau’ofa and asks: “[i]nstead of seeing isolated islands of national languages and literatures, what if we opened our eyes and ears to the noisy ocean of translation out of which those islands emerge?”

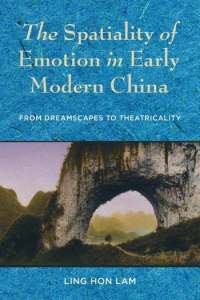

Ling Hon Lam encourages us to think of emotions in terms of space; when we sympathize with a character in a play or feel something for another person, that emotion takes place, for it moves us outside ourselves. In Chinese this relation between space and emotion is described by the term qingjing; a scenery of feeling or in Ling’s translation an “emotion-realm”.

Ling Hon Lam encourages us to think of emotions in terms of space; when we sympathize with a character in a play or feel something for another person, that emotion takes place, for it moves us outside ourselves. In Chinese this relation between space and emotion is described by the term qingjing; a scenery of feeling or in Ling’s translation an “emotion-realm”.