My review was first publish in Cha: An Asian Literary Journal on September 1st, 2022.

Monika Gaenssbauer and Nicholas Olczak (editors). Of Forests and Humans: Hong Kong Contemporary Short Fiction. Edition Cathay, vol. 74, Bochum, Projekt Verlag, 2019.

In Of Forests and Humans, Monika Gaenssbauer and Nicholas Olczak present anglophone readers with the narrative experimentation, complex urbanism and literary variety of contemporary fiction from Hong Kong. The volume contains six well-chosen short stories published between 1992 and 2011 and introduces a variety of different literary styles, from Xi Xi’s 西西 surreal fabulations in “Elzéard Bouffier’s Forest” to Chan Lai Kuen’s 陳麗娟 science-fiction-flavoured urban labyrinths in “E6880**(2) from Block 6, building 20, wing E”.

Each short story is followed by a close reading by the editor-translators, which provides cultural and historical context, suggestions for relevant theoretical approaches, as well as their reading of the piece. This is meant as a pathway into the text rather than a definitive interpretation, for, as the editors rightly acknowledge, the “strength of many of the stories in this collection [is] that they might draw very different responses and interpretations from different kinds of readers”. For instance, where Gaenssbauer and Olczak were reminded of Friedrich Dürrenmatt’s short story “The Tunnel” when reading Wang Pu’s 王璞 “Greek Sandals”, an image from “The Tunnel” in Akira Kurosawa’s 1990 film Dreams instantly surfaced in my mind when I read the story. It is interesting that the symbolic structure of the tunnel often used to represent the link between conscious wakefulness and subconscious longings and emotions so readily solicits personal and immediate responses in different readers. If Hong Kong literature has a common denominator despite its plurality of forms and voices, it is the willingness to embrace and invite, at times even demand, multiple, contrasting and complicated readings.

As the editors note, Xi Xi’s story is intertextual in setting, writing itself into and through Jean Giono’s “The Man Who Planted Trees”. It is a story of the cyclical withering and rebirth of a utopian forest, half-hearsay, half-imaginary, and slowly being translated, it forms the memory of the second-person protagonist’s father through the protagonist’s sensory experiences and onto the pages of the story. This situates the story firmly on the boundary between memory and fiction, and reality and imagination, allowing us to read it as a metafictional comment on how such processes become intertwined in literary narratives. The story also has an ecocritical aftertaste when, in the space of a single page, the utopian forest of the father’s recollections comes to life only to dry up again: “Elzéard Bouffier’s forest unfolded like a flower, this green sea of trees changed the area into a paradise where people lived peacefully […] The dried out well also came to life again […]” and a few lines further down, “the last drops of water had dried up, the river turned into a clay-grey canal. You did not know what had happened in the meantime to turn the gardens into a wasteland and make Elzéard Bouffier’s forest completely disappear.” Several utopian intertexts spring to mind, including Tao Yuanming’s 陶淵明 famous fable “Peach Blossom Spring”, which depicts a hidden site where human society has been preserved in its natural and unspoiled state. At the same time, it is also metatextual, describing how the reading experience brings to life the forest of memory that has all but disappeared with time. In the end, when the protagonist arrives at the barren memory of a long-gone forest and finds the last of Bouffier’s acorns, the cycle is ready to start over as the seeds sprout a new story, a new life.

Several of the stories experiment with the popular genre of urban romance, but they do so in completely unexpected ways by delving into darker aspects of city life. This includes depictions of deadly violence in Jessie Chu’s 朱艷紅 “Wonderland”, a story that flirts with the genre of hard-boiled detective fiction without giving in to any of the clichés. Instead, it uses the crime fiction format to explore contrasting yet intermingled experiences of alienation and proximity in a global big city.

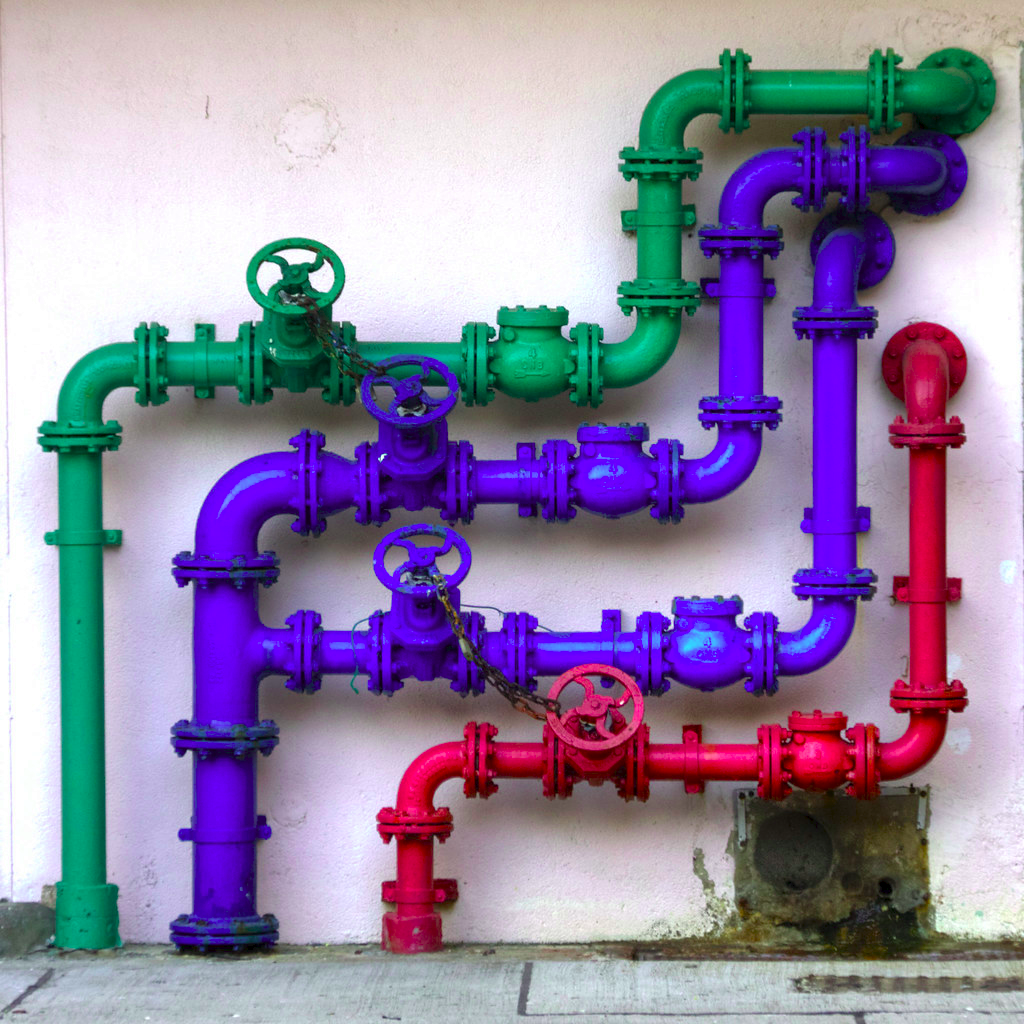

Hon Lai-chu’s 韓麗珠 “Water Pipe Forest” is sublime in its depiction of the city-body, using as it does the image of plumbing to form a corporeal link between human interior and urban exterior. At the same time as the building across from the narrator-protagonist’s home is demolished due to faulty plumbing and bursting pipes, her grandmother is admitted to hospital with a gastric ailment establishing a symbolic parallel. On a more explicit note, the narrator identifies directly with her building through the similarity between water pipes and gastric tubes: “On the fourth day without water I still heard no noise in the water pipe. I felt restless, as if part of my body was missing.” Playing with sensory perceptions of watery noises gurgling through buildings and bodies, the story replicates and reverses the relationship between citizen and city in the relationship between reader and text. Just as the sound of water in the pipes recalls and affirms the protagonist own body, so does the watery symphony of the text resound in the body of the reader.

Of Forests and Humans promises to be a great resource for students of literature, Chinese studies, and/or translation studies, yet I can’t help wishing that the editors had opted for a bilingual text. This would have allowed curious anglophone readers to acquaint themselves with traditional characters while enjoying high-quality literature and to explore the paths chosen by the translators as a practical exercise in translation. Despite this omission, the fact that the original title and source of each story is given at the end of each translation is a terrific help that will permit readers to pursue analyses of the original texts or follow up on other works by the authors showcased in this collection. The bibliography at the end of the volume likewise provides a good starting point for readers who want to engage theoretically and historically with Hong Kong literature.

Read together, these stories are examples of innovative approaches to genres such as urban romance, science fiction, crime fiction and showcase the diversity and originality of Hong Kong literature. The editors have wisely included highly celebrated as well as lesser-known authors, ensuring there is something for both veterans and newcomers to explore. Some of the translations feel a little stiff while others offer a smoother read and in a few instances something appears to have gone wrong in the typesetting, baffling the reader with recurring light-grey bits of text.

The title Of Forests and Humans, as well as providing a thematic focus on the jungle-like qualities of urban life, creates an anticipation of narrative engagements with the spatial that are both organic and unconventional, an expectation the stories each fulfil in their individual way. Here, skyscrapers rise like huge tree trunks above the humans navigating the dynamic and metamorphous cityscape. People look at one another’s faces and see overlapping images of intimate strangers and alienated kinfolk. Readers get lost in unfamiliar storylines, only to glimpse their own memories at every fictional street corner. There is certainly enough to discover and celebrate in contemporary Hong Kong literature and now a little more of it is available in English.

How to cite: Møller-Olsen, Astrid. “Stories Grow in Hong Kong: A Review of Of Forests and Humans.” Cha: An Asian Literary Journal, 01 Sept. 2022, chajournal.blog/2022/09/01/forests-and-humans/