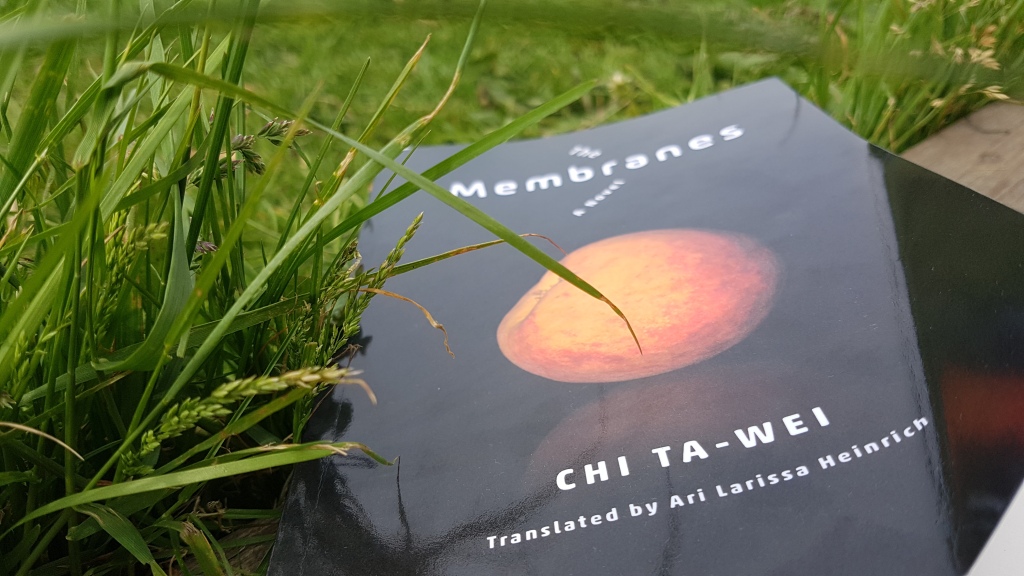

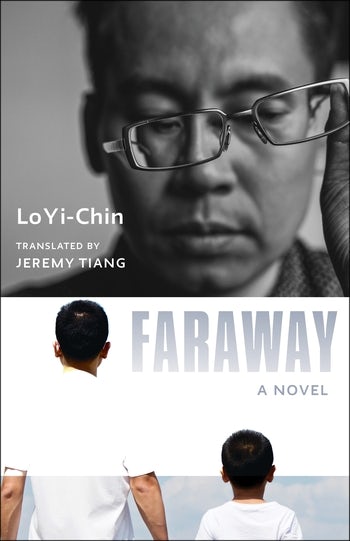

Lo, Yi-Chin. Faraway. Translated by Jeremy Tiang. Columbia University Press: 2021.

Faraway is a story of transitions: between life and death, between losing a parent and becoming one. In Jeremy Tiang‘s able translation a further set of transitions take place: between reader and writer (the translator starts out as one and becomes the other), between one language and another.

The novel chronicles Taiwanese protagonist Lo Yi-Chin’s (the author’s fictionalized counterpart) struggle with health care bureaucracy as he does his best to bring home his comatose father who has suffered a massive brain hemorrhage while holidaying in mainland China.

The holiday was the elder Lo’s first return to his ancestral Jiangxi province (and to the Chinese mainland) since 1949 when he left his first wife and son behind and fled to Taiwan with the Kuomintang troops. After his stroke, the trip that began as a homecoming transitions into an awkward meeting between two long-separated branches of the Lo clan: the Taiwanese family and their mainland relatives.

Reading Faraway, I felt constantly curious about what the women of this drama felt. Did the abandoned first wife feel resentful towards her younger and more affluent successor? Or curios about her faraway lifestyle? How did she feel about having to recognize and treat as head of the extended family this man whom she had not seen for more than half a century? How did the Taiwanese wife feel about being confronted with a stepson only a decade younger than herself? And, perhaps most of all, I wondered about the protagonist’s own wife, left behind in the final stages of pregnancy in an echo of his father’s abandonment of his first wife.

But this is a story of fathers and sons. Of the life-changing transition from being someone’s son to being someone’s father. Of the baffling responsibility of suddenly finding yourself the stand-in for the debilitated patriarch, head of a large family you hardly know, much less understand.

One of the lingering tastes that characterizes Faraway is irony. The narrative exposes both the blatant prejudice that the urbane, Taiwanese protagonist feels for his hillbilly mainland relatives and the ambivalent emotions of indebtedness and contempt they evoke in him.

This theme is poetically mediated through continuous references to primeval lifeforms. Such imagery is used to signify the mental regression of the father after his brain hemorrhage – “this old man, so stuffed full of tubes, like a fossilized crawling bug” – as well as the protagonist’s mainland roots, so distant and primitive they seem almost prehistoric.

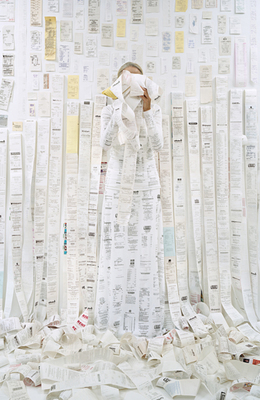

by Rachel Perry Welty,

MIT List via Cuseum

My overall impression of the novel is a very dense narrative, a paper river overflowing with a tremendous number of tedious details upon the waves of which glitter sudden bursts of simple and breathtaking literary beauty, confidently and delicately translated by Tiang: “I stood behind her, gazing at her profile, which was very like my wife’s but drawn with a thicker pencil. She told this story in the gloom, leaving indelible marks of sadness.”

And the boring and excessive details are there for a reason. Collectively they make up the form and shape of despair. Faraway is the fictionalized account of Lo Yi-Chin’s own experiences of the deep grief and eyewatering paperwork associated with a sudden and serious illness abroad. Rather than spelling out the emotional responses of the main characters, the narrative expresses the feelings of abandonment, meaninglessness, and Kafkaesque bewilderment through painstakingly detailed accounts of everyday consumption and bureaucracy.

Lo’s style is cinematic, a style that his fictional counterpart seems to share according to one of his friends, who asks him “Hey, Lo, how come your stories are so weird – all those characters with blurry faces running around huge, empty, ‘abandoned’ spaces?” Both author and narrator are drawn to “no-places” (such as airports or hospitals) where, outwardly, nothing much happens, but emotionally, everything is at stake. And they convey this duality through terse narrative teeming with supposedly unimportant little details floating upon, and concealing, an ocean of emotions beneath.

And the faces of the novel’s characters do seem blurred. If we get to know the narrator -the camera man of the cinematic narrative- at all, it is through his framing of the views we are presented with. Everything else remains a background of blurred faces.

The perfect filmic ending comes at page 227, when the narrator walks into the sunset with his son: “In this way, I led this beloved person sadly through a landscape of true emptiness, the outlines of our faces blurring into shadow in the faint light.” Here, all the metafictional elements come together in a shot of the father and son surrounded by emptiness, blurred into archetypes.

But the novel doesn’t end here. In reality, death is often messy, disgusting, boring, fatiguing, and drawn-out. And so, Faraway continues to tell the story of a fatherless man who struggles to be a father amidst the absurd chaos of everyday life, of a young boy for whom death is now a recurring part of life. The text ends in a horrible shopping mall, littered with grotesque animal corpses discarded as consumer goods. The transitions continue, hopefuly with more of Lo’s work in translation.

Read an English translation of Lo’s “The Body Transporter” here.