This summer, I travelled to Napoli for one of the most enjoyable scholarly gatherings I’ve attended in a long time – a two-day symposium on Genealogies of Literary Form in Contemporary China beautifully organised by Marco Fumian.

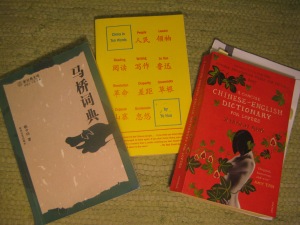

I had a lot of amazing (vegetarian!) food plus inspiring (and entertaining) conversations on top of which I got to present my paper “Fragments of Hong Kong: Collage, Archive, Dictionary,” in which I trace a tendency towards fragmented formats in contemporary literary works from Hong Kong and relate it to ongoing identity politics in the city. Through narrative analyses of Sai Sai’s 西西 My City 我城 (1975), Dung, Kai-cheung’s 董啟章 Atlas 地圖集 (1997), and A Dictionary of Two Cities I–-II 雙城 辭典I-II (2012) by Hon Lai Chu 韓麗珠 & Dorothy Tse 謝曉虹, I arrive at a typology of fragmented formats that includes the collage, the archive, and the dictionary, and which represent different but related strategies for literary experimentation with polyphonic, anti-essentialist approaches to Hong Kong identities.

The Napoli All Stars:

- Paola Iovene (University of Chicago), “Reading Beyond Books: Airing Lu Yao”

- Marco Fumian (Oriental University, Naples), “Methods of Distancing and the Limits of Realism in Contemporary China”

- Nicoletta Pesaro (Ca’ Foscari University, Venice), “From the Avantgarde to the Unnatural Narrative: Can Xue’s Fictional World and its Political Meaning”

- Wendy Larson (University of Oregon), “Not Italian Opera: Mo Yan’s Sandalwood Death and the Scourge of Western Literary Models”

- Paolo Magagnin (Ca’ Foscari University, Venice), “Chinese Stories for Global Young Readers: a Look at the Cao Wenxuan Phenomenon”

- Pamela Hunt (University of Oxford), “A Wider and Stranger Space”: Xue Yiwei’s World-Shaped Literature”

- Astrid Møller-Olsen (Lund University and University of Stavanger), “Fragments of Hong Kong: Collage, Archive, Dictionary”

- Jiwei Xiao (Fairfield University), “The Talk of the Town: Chitchats in Xijie xiaoshuo and Cinema”

- Lena Henningsen (University of Freiburg) “Transformations of a Literary Giant: The Re-Writing of Lu Xun and his Works in Chinese Lianhuanhua Comics”

- Daria Berg (University of St. Gallen), “Genealogy of Utopia and anti-Utopia in Chinese literature”

- Martina Codeluppi (University of Insubria, Como), “What about Climate Change? The Underdeveloped Branch of Chinese Cli-Fi”

- Mingwei Song (Wellesley College), “New Wonders of a Nonbinary Universe: Genders of Chinese Science Fiction”

Through the story the people of the village succeed in making the protagonist recall the violent and suppressed happenings of his past life in the village where he lived as an ‘educated youth’ and maybe killed a man. Indeed it is an act of re-membering of bringing something back into the mind, for before they start calling him by his old name ‘Glasses Ma’, he is completely unaware that he has not always been Huang Zhixian.

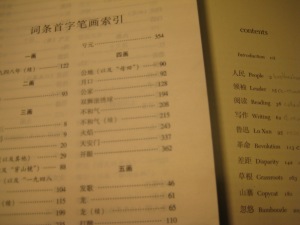

Through the story the people of the village succeed in making the protagonist recall the violent and suppressed happenings of his past life in the village where he lived as an ‘educated youth’ and maybe killed a man. Indeed it is an act of re-membering of bringing something back into the mind, for before they start calling him by his old name ‘Glasses Ma’, he is completely unaware that he has not always been Huang Zhixian. In Dictionary the official historical narrative is distorted and the constructedness of its raw linguistic framework exposed by the local dialect and its (mis-)appropriations of official discourse.

In Dictionary the official historical narrative is distorted and the constructedness of its raw linguistic framework exposed by the local dialect and its (mis-)appropriations of official discourse.