On Tuesday January 21st I defended my doctoral dissertation “Seven Senses of the City: Urban Spacetime and Sensory Memory in Contemporary Sinophone Fiction” at the Centre for Languages and Literature, Lund University, Sweden.

In Sweden, the defense is a public event, a critical dialogue between the doctoral candidate (me in this instance) and an external opponent (the wonderful prof. Jie Lu from University of the Pacific).

In Sweden, the defense is a public event, a critical dialogue between the doctoral candidate (me in this instance) and an external opponent (the wonderful prof. Jie Lu from University of the Pacific).

After a short apology that my work (despite ostensibly constituting a multisensory approach to the study of memory and literature) did not include any perfume sniff pads, CD soundtracks or an eatable book cover, prof. Lu graciously introduced the main arguments and contributions of my dissertation. This took care of the first half hour.

Prof. Lu then asked me several critical questions to do with possible incongruities or alternative paths my research might have taken, producing a very rich and fruitful discussion of another hour. Finally the three esteemed scholars of the examining committee, Prof. Lena Rydholm from Uppsala Uni, senior lecturer Martin Svensson Ekström and prof. Rikard Schönström, presented briefly their comments on the dissertation and we all went out to await their decision.

Prof. Lu then asked me several critical questions to do with possible incongruities or alternative paths my research might have taken, producing a very rich and fruitful discussion of another hour. Finally the three esteemed scholars of the examining committee, Prof. Lena Rydholm from Uppsala Uni, senior lecturer Martin Svensson Ekström and prof. Rikard Schönström, presented briefly their comments on the dissertation and we all went out to await their decision.

In short, they liked it a lot and awarded me my doctoral degree and we all had sparkly wine or sparkly apple cider (and I had a beer) and hooray what a day.

Below, you will find a painfully short abstract of what is really a 260 pages long analytical kaleidoscope that took me more than four years to complete:

![20200128_104017[1]](https://writingchina.files.wordpress.com/2020/01/20200128_1040171.jpg?w=216&h=288) What happens when the city you live in changes over night? When the streets and neighborhoods that form the material counterpart to your mental soundtrack of memory suddenly cease to exist? The rapidly changing cityscapes of Taipei, Hong Kong and Shanghai form an environment of urban flux that causes such questions to surface in literary texts.

What happens when the city you live in changes over night? When the streets and neighborhoods that form the material counterpart to your mental soundtrack of memory suddenly cease to exist? The rapidly changing cityscapes of Taipei, Hong Kong and Shanghai form an environment of urban flux that causes such questions to surface in literary texts.

In this dissertation, I engage with themes of scented nostalgia, flavors in fiction, walking as method, literary cartography, the melody of language, gendered cityscapes, metafictional dreams and rhythmic senses of time to study how contemporary cities change the way we think about time, space and memory.

As most of you will know, this year marks the one hundredth anniversary of the May Fourth or New Culture Movement in Chinese history. I was fortunate enough to be invited to two Swedish celebrations of the centennial with each its animated discussion of the movement’s legacy.

As most of you will know, this year marks the one hundredth anniversary of the May Fourth or New Culture Movement in Chinese history. I was fortunate enough to be invited to two Swedish celebrations of the centennial with each its animated discussion of the movement’s legacy.

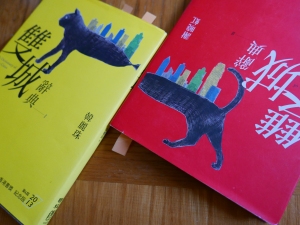

I specifically analysed the chapter “Swallow and Spit” (吞吐) from Dorothy Tse 謝曉虹 and Hon Lai Chu’s 韓麗珠 double novel A Dictionary of Two Cities 《雙城辭典》 from 2012, in which urban existence is represented through an alimentary vocabulary, with machines that “eat” coins, and pedestrians who are “eaten by the crowd.” In their fictional world, sexual intercourse becomes an act of “devouring” while babies are “vomited” out and education is seen as a process of digestion, where “raw” children enter, and processed citizens are excreted.

I specifically analysed the chapter “Swallow and Spit” (吞吐) from Dorothy Tse 謝曉虹 and Hon Lai Chu’s 韓麗珠 double novel A Dictionary of Two Cities 《雙城辭典》 from 2012, in which urban existence is represented through an alimentary vocabulary, with machines that “eat” coins, and pedestrians who are “eaten by the crowd.” In their fictional world, sexual intercourse becomes an act of “devouring” while babies are “vomited” out and education is seen as a process of digestion, where “raw” children enter, and processed citizens are excreted.