This review was first published in Cha: An Asian Literary Journal, 18 May 2023, chajournal.blog/2023/05/18/diasporic

Soon Ai Ling’s short stories weave cultural trajectories from Guangdong, Hong Kong, the UK, Malaysia, and Singapore into a rich fabric of personal experiences and artistic passions. Each story centres around a particular craft, from which vantage point it explores the relationships between cultural heritage and innovation, and between past and future homelands. As each story generates its own pattern, the variety of Chinese-speaking diasporas is showcased, as well as the internal diversity of dynastic China and of the PRC today. In Diasporic, cultural influence is not a unilinear movement from an imagined core to a perceived periphery but rather a continuous process of artistic experimentation and cross-cultural inspiration that is inextricably entwined with personal histories of migration.

In the story “Batik Melody”, the protagonist comes to Malaysia to take over the family batik factory now run by his father’s second wife Aisha and her daughters, only to realise that the dreary old family business is actually an innovative cross-cultural playground: “it dawned upon me that they had inherited not only their mother’s cultural heritage, but also learned a lot from Father” (59). The marriage between Aisha and his father is also a symbolic union of two (or rather several) cultural traditions, bringing together a variety of approaches to artisanal work. On the one hand, Aisha—who is of Arab and Chinese descent—stands for the practical approach. She owns and runs the factory with her daughters, who are both highly creative and innovative when it comes to inventing new patterns and techniques. The protagonist’s father, on the other hand, was a craft historian working on a book about the history of batik. From his Miao-Chinese ancestors, he inherited an extensive knowledge of plant dyes and he represents the more intellectual aspects of batik production. Between his father’s historical interests and Aisha’s hands-on approach, the protagonist, who was educated in the UK, struggles to find his own place in the factory until he decides to focus on marketing. Like the colourful cloth they produce, the lives of the characters are coloured by many cultural influences and traditions, coming together to form new patterns and new stories.

Soon’s writing combines the subtle yet powerful pathos and social critique of Eileen Chang with a literary celebration of everyday life, peppered with glimpses of history with a capital H, reminiscent of Xi Xi’s plain leaf literature. Like Xi Xi, Soon foregrounds personal affairs but allows glimpses of momentous historical events slip through, such as the tide of emigration following the Tiananmen Square Massacre in 1989: “On my way home, the sound of the nightly news wafted through from TV sets behind store windows, reporting that tomorrow the British would announce how many Hong Kongers would receive the permit to be UK citizens” (38). Yeo Wei Wei’s direct translation of wonderful nicknames like “Carefree Yu” and “Frost Liu” also add to the delightfully Xi Xi-esque atmosphere.

Soon’s stories honour the artistic and creative side of artisanal crafts using individual characters with a flair for, and loyalty toward, their work as the red thread through the fabric of the compilation. In “Jade Butterflies”, Soon takes advantage of the close association between craftsperson and crafted object to critique the commodification and exploitation of (often women) workers. By writing about the intangible cultural craft of opera, whose product—song—cannot be separated from the person producing it, she makes her point even stronger, as the protagonist puts it “We are not goods. Buy us out? You think you have so much power. If we don’t agree, you won’t be able to buy us out either” (123). Despite the culturally sanctioned practice of “buying out” singers to become concubines, the protagonist insists that she has, if not absolute choice, then at least the right of veto.

Later in the story, Soon uses the same symbolic identification of craftsperson and artwork to comment on the objectification of women as aesthetic ornaments of pleasure and entertainment. She lets the male protagonist and “philanthropic protector” of young opera singers realise that his singing concubines are not mere ornaments but whole persons: “‘I thought the two of you sang for enjoyment. How did singing a bit of opera lead to all these tears?’ ‘All of you think that opera is fun and entertainment. You don’t realise that our singing comes from our hearts” (111). The pretty face and pleasing voice of the opera singer hides a complex person with a life of pain, pleasure, and hard work. In this way, Soon reverses the objectification process so that the artist is revealed as more than a human knitting machine and the crafted artwork is understood to hold their passions and memories. The emotive power of lovingly crafted objects is a theme that recurs throughout the compilation, like the scene where a handful of jade butterfly buttons given at a lovers’ parting in Guangdong turns up in Singapore half a century later and helps the long-lost lovers reunite: “Ah! Those jade butterflies, those jade buttons, they were like spirits, drawing this relationship, which had spanned half a century, to a satisfying conclusion” (133).

Yeo Wei Wei’s translation combines the softness of the many moving stories with a sense of structural stiffness, like a piece of beautifully embroidered cloth. It also lends the stories a slightly old-fashioned air that is quite charming, like listening to your grandmother reminisce about her youth.

In Diasporic, processes of intercultural exchange are explored through chronicles of craft and reveal the inherent diversity of the misleadingly singular noun culture: “I learnt that embroidery started thousands of years ago. I learnt that the goods we made were sold not only in China, but also in other countries, that they were exported and even sent to competitions abroad. I learnt that apart from Guangdong or Yue embroidery, there is also Xiang or Hunan embroidery, Su or Suzhou embroidery, and Shu or Sichuan embroidery; Guangdong embroidery encompassed the embroidery produced in workshops like ours, as well as that of the women at home in the city and countryside, and the Li tribe on Hainan Island” (97). Like the artisanal crafts it celebrates, the craft of writing that Diasporic embodies is a cross-cultural product of multilingual experiences and multiple mutable translations that continues its journey into new languages and new lives.

How to cite: Møller-Olsen, Astrid. “New Languages and New Lives: Soon Ai Ling’s Diasporic.” Cha: An Asian Literary Journal, 18 May 2023, chajournal.blog/2023/05/18/diasporic

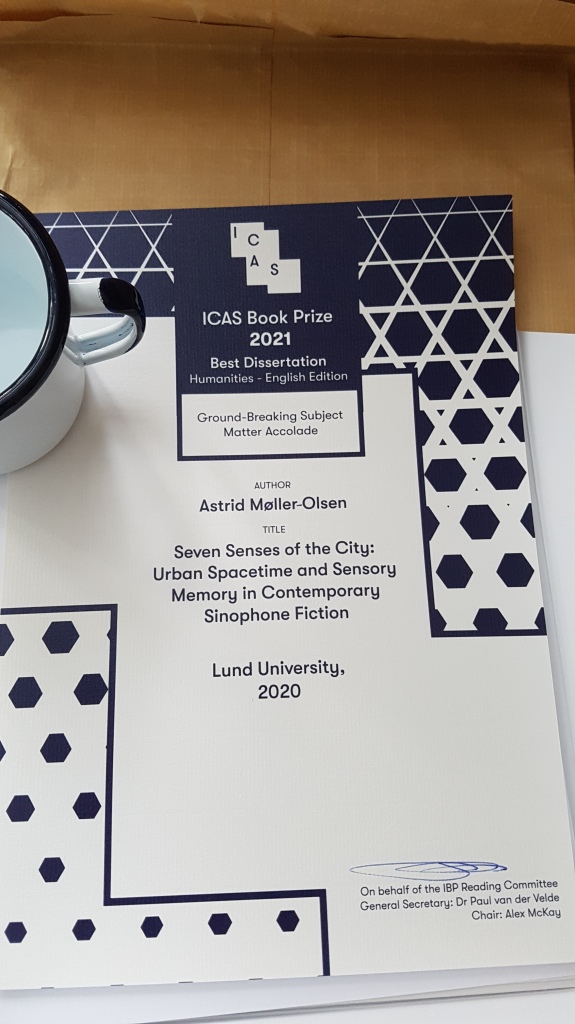

In Sweden, the defense is a public event, a critical dialogue between the doctoral candidate (me in this instance) and an external opponent (the wonderful

In Sweden, the defense is a public event, a critical dialogue between the doctoral candidate (me in this instance) and an external opponent (the wonderful  Prof. Lu then asked me several critical questions to do with possible incongruities or alternative paths my research might have taken, producing a very rich and fruitful discussion of another hour. Finally the three esteemed scholars of the examining committee,

Prof. Lu then asked me several critical questions to do with possible incongruities or alternative paths my research might have taken, producing a very rich and fruitful discussion of another hour. Finally the three esteemed scholars of the examining committee, ![20200128_104017[1]](https://writingchina.files.wordpress.com/2020/01/20200128_1040171.jpg) What happens when the city you live in changes over night? When the streets and neighborhoods that form the material counterpart to your mental soundtrack of memory suddenly cease to exist? The rapidly changing cityscapes of Taipei, Hong Kong and Shanghai form an environment of urban flux that causes such questions to surface in literary texts.

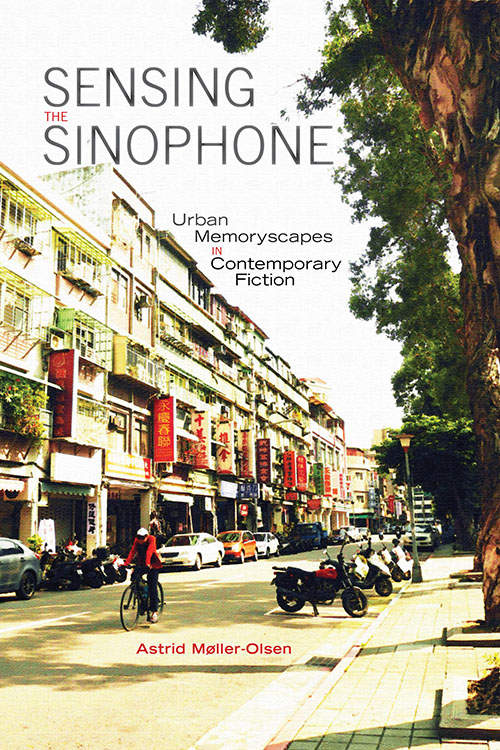

What happens when the city you live in changes over night? When the streets and neighborhoods that form the material counterpart to your mental soundtrack of memory suddenly cease to exist? The rapidly changing cityscapes of Taipei, Hong Kong and Shanghai form an environment of urban flux that causes such questions to surface in literary texts.

“With a number of twists and turns, the tram skirts Victoria Park and the Tin Hau Temple (one of Hong Kong’s oldest) on its way to North Point, Quarry Bay, and Shau Kei Wan at the eastern tip of the island. The ride is convenient, if not comfortable, and the panorama of buildings and people moving by in slow motion gives one the feeling of travelling backward through time – a nostalgic antidote for the stomach-churning, competitive pace of Central Business District.”

“With a number of twists and turns, the tram skirts Victoria Park and the Tin Hau Temple (one of Hong Kong’s oldest) on its way to North Point, Quarry Bay, and Shau Kei Wan at the eastern tip of the island. The ride is convenient, if not comfortable, and the panorama of buildings and people moving by in slow motion gives one the feeling of travelling backward through time – a nostalgic antidote for the stomach-churning, competitive pace of Central Business District.”