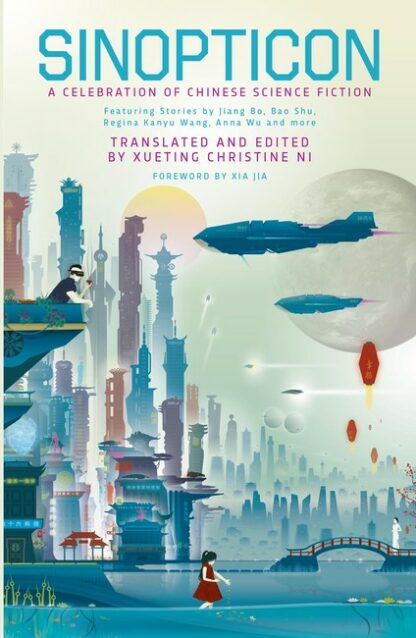

Sinopticon is the brainchild of Xueting Christine Ni who has done an amazing work of collecting, translating, and introducing 13 new SF stories from contemporary China. The stories span two decades and incorporate a variety of themes from galactic existentialism in Han Song’s “Tombs of the Universe” (宇宙墓碑 1991) to Ma Boyong’s hardboiled-style space age take on Chinese holiday traffic chaos in “The Great Migration” (大冲运 2021).

The overweight of male protagonists, casual gender stereotyping, and the odd dash of not too subtle patriotism made me a bit tired at times, but luckily several of the stories depart from this pattern. Jiang Bo’s “Starship: Library” (宇宙尽头的书店) combines a structure reminiscent of Jorge Luis Borges’s “The Library of Babel” with Arthur C. Clarke’s Monolith in 2001 A Space Odyssey to explore the difference between knowledge and learning. I prefer Ni’s evocative title over the more literal translation “the bookshop at the end of the universe” (the Douglas Adams reference is getting a little worn), and the idea of a roaming library piloted by a contemporary incarnation of an ancient Chinese goddess will excite bibliophiles of all galaxies.

Each story is followed by an anecdotal epilogue introducing the author and offering a mini-interpretation of the narrative, which, combined with foot notes explaining Chinese terms and idioms as well as a list of author bios at the end of the book, is a bit too much guidance for my taste. But who am I to talk, I’m offering up my own readings all the time including right now. Anyway, one can just skip on to the next story.

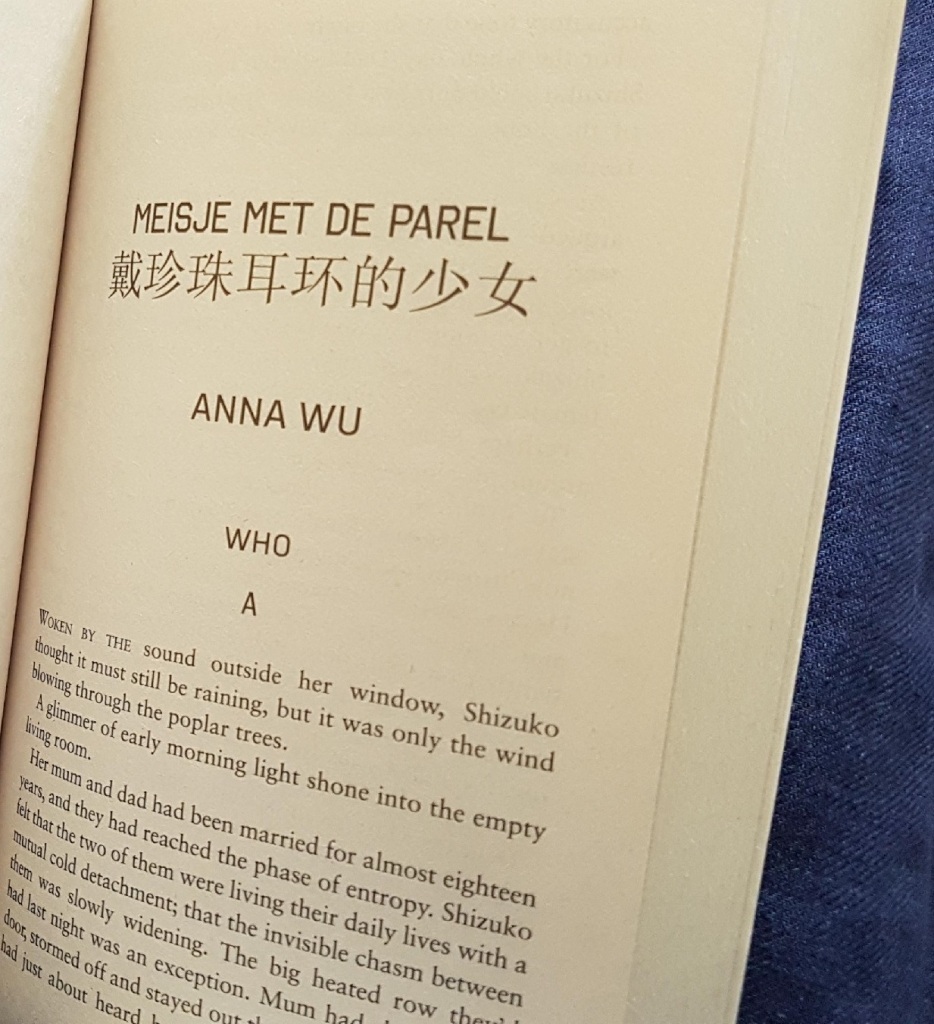

Other interventions are more fruitful, like the decision to title Anna Wu’s story “戴珍珠耳环的少女” (the girl with the pearl earring) in the original Dutch as “Meisje met de Parel” to avoid confusion with other literary and cinematographic works inspired by of Vermeer’s painting. Adding another language to the layers of time and pigments that envelop the story only makes the fabric of the narrative more intriguing. Each English title is subtitled by the original Chinese title, which, as well as being is enormously helpful for researchers, is also a simple and beautiful way of reminding the reader of the multiplicity of languages and people involved in bring these stories to them.

Recurring topics include a renewed appreciation for the cultural history of Earth stemming from a futurist and/or intergalactic perspective in Han Song and Tang Fei’s stories, posthuman explorations of the humaneness of cyborgs in Wang Jinkang and Nian Yu’s work, and new regimes for AI that include social intelligence (Hao Jingfang) and process-oriented learning (Jiang Bo). An interesting deviation from classic SF figures of robots and spaceships is A Que’s “Flower of the Other Shore” (彼岸花) – an ecocritical zombie story featuring a Rome and Juliet romance between an “uncontaminated” (not yet subjected to the zombie virus) human woman and a male protagonist who is a hybrid between a Chinese jiangshi (僵尸 stiff corpse/jumping vampire) and a Hollywood zombie. Xueting Christine Ni talks about this story in the most recent episode of the Sinophone Unrealities podcast available here.

I definitely enjoyed some stories more than others, but all in all, am delighted and grateful to Ni and her crew for all their work in making this beautiful collection of authors and stories available to an Anglophone audience: A new addition our collective starship library.

TOC

Foreword, Xia Jia

Introduction, Xuenting Christine Ni

The Last Save, Gu Shi

Tombs of the Universe, Han Song

Qiankun and Alex, Hao Jingfang

Cat’s Chance in Hell, Nian Yu

The Return of Adam, Wang Jinkang

Rendezvous: 1937, Zhao Haihong

The Heart of the Museum, Tang Fei

The Great Migration, Ma Boyong

Meisje met de Parel, Anna Wu

Flower of the Other Shore, A Que

The Absolution Experiment, Bao Shu

The Tide of Moon City, Regina Kanyu Wang

Starship: Library, Jiang Bo