As most of you will know, this year marks the one hundredth anniversary of the May Fourth or New Culture Movement in Chinese history. I was fortunate enough to be invited to two Swedish celebrations of the centennial with each its animated discussion of the movement’s legacy.

As most of you will know, this year marks the one hundredth anniversary of the May Fourth or New Culture Movement in Chinese history. I was fortunate enough to be invited to two Swedish celebrations of the centennial with each its animated discussion of the movement’s legacy.

The first was held at the Royal Swedish Academy of Letters, History and Antiquities in Stockholm in September. Our two-day symposium was organised by Torbjörn Lodén, Lena Rydholm and Fredrik Fällman and included addresses from Xu Youyu 徐友渔, Vera Schwarcz, Zhang Longxi 張隆溪, Jae Woo Park 朴宰雨, Bonnie S. McDougall, Jyrki Kallio, Monika Gänssbauer, Qin Hui 秦晖, Wang Ning, Erik Mo Welin, Ming Dong Gu, Liu Jiafeng and myself.

Vera Schwarcz and Monika Gänssbauer

Zhang Longxi considered classical Chinese and European literary theory comparatively through the shared understanding of art as a product of, if not pain, then adversity in some form or other. He exemplified this through an examination of the image of the oyster, whose beautiful pearl is a product of the presence of a hard grain of sand in its soft interior.

Bonnie McDougall presented an original addition to our understanding of literary censorship as something that is not only political but also be aesthetic. By comparing Lu Xun’s published correspondence with Xu Guangping to the original letters, she was able to show that (contrary to how their relationship is presented in the version revised for publication) in the uncensored letters, Xu comes across as the more assertive and the one taking the initiative.

Ming Dong Gu, Wang Ning, Jyrki Kallio

In October, we had a smaller symposium in Uppsala, where Mingwei Song presented his inspiring reading of Lu Xun’s A Madman’s Diary as a work of science fiction and traced Lu’s legacy of curing cultural ailments through literature to contemporary writers such as Han Song and Liu Cixin.

On both occasions, I presented my work on man-eating as a contemporary motif that has developed from Lu Xun’s use of various types of cannibalism as a way of criticising feudal society, over Yan Lianke and Mo Yan’s narrative invocations of vampirism and “meat-boys” to criticise political and economic corruption, to the representation of mega-cities as anthropophagus superstructures in contemporary urban fiction.

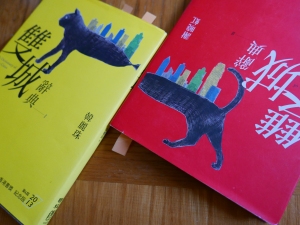

I specifically analysed the chapter “Swallow and Spit” (吞吐) from Dorothy Tse 謝曉虹 and Hon Lai Chu’s 韓麗珠 double novel A Dictionary of Two Cities 《雙城辭典》 from 2012, in which urban existence is represented through an alimentary vocabulary, with machines that “eat” coins, and pedestrians who are “eaten by the crowd.” In their fictional world, sexual intercourse becomes an act of “devouring” while babies are “vomited” out and education is seen as a process of digestion, where “raw” children enter, and processed citizens are excreted.

I specifically analysed the chapter “Swallow and Spit” (吞吐) from Dorothy Tse 謝曉虹 and Hon Lai Chu’s 韓麗珠 double novel A Dictionary of Two Cities 《雙城辭典》 from 2012, in which urban existence is represented through an alimentary vocabulary, with machines that “eat” coins, and pedestrians who are “eaten by the crowd.” In their fictional world, sexual intercourse becomes an act of “devouring” while babies are “vomited” out and education is seen as a process of digestion, where “raw” children enter, and processed citizens are excreted.

While certain themes of the New Culture Movement are still alive and thriving today, contemporary global society presents a changed environment that enable and demand writers to rediscover, reinvent and revolutionize modern motifs in new and enlightening ways.