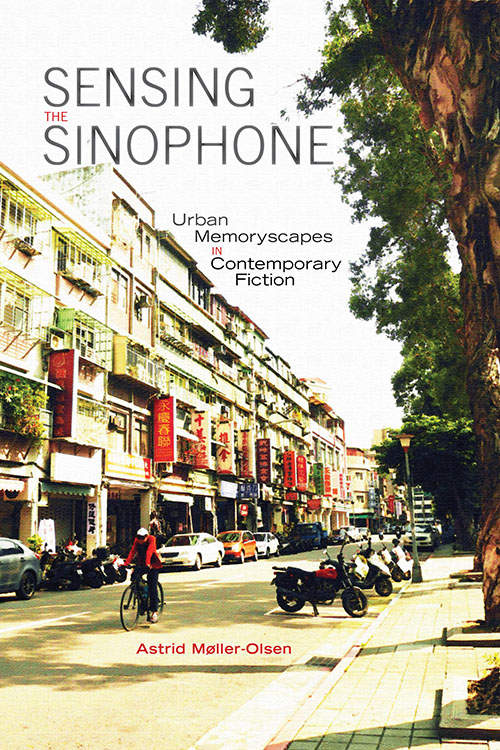

The first section of my new monograph Sensing the Sinophone: Urban Memoryscapes in Contemporary Fiction (Cambria 2022) I call the SKELETON because it provides the structure for the book. It consists of 1) the theoretical foundations for the analyses inlcuding an introduction to literary spacetime and alternative sensoria and 2) my triangular approach to comparative literature and an introduction to the six primary texts analysed throughout the book.

Chapter 2. The Three-City Problem: A Kaleidoscope of Six Works

I begin by borrowing Liu Cixin’s Three-Body problem (which he, in turn, has borrowed from mathematical physics) and convert it into a three-city problem. While the interaction between two bodies poses a relatively simple problem, the addition of a third body of approximately equal mass complicates calculations immensely. Likewise, a literary triangular comparison creates more junctions and convergences than a twofold one. Furthermore, “it frustrates any tendency towards binarism (be it East-West or North-South) and complicates notions of internal homogeneity by centering on cultural interchange as constitutive for our understanding of place” (Sensing the Sinophone, 24).

I then sketch out recent discussions on the form and content of Sinophone literature and add my own triangular urban approach – focusing on the three cities of Hong Kong, Taipei, and Shanghai that are all (to various extents) culturally and linguistically hybrid cities with (semi)colonial pasts. These three cities constitute sites of negotiation between strong urban identities and (contested) ties to mainland China, and act as individual anchors for both regional and international networks.

Finally, I introduce the six literary works that I analyse comparatively throughout the book (rather than relegating each to its own chapter), namely:

Shanghai: Chen Cun 陈村. Xianhua he 鲜花和 [Fresh flowers and] and Ding Liying 丁丽英. Shizhong li de nüren 时钟里的女人 [The woman in the clock].

Taipei: Chu T’ien-hsin 朱天心. Gudu 古都 [The Old Capital] and Wu Mingyi 吳明益. Tianqiao shang de moshushi 天橋上的魔術師 [The magician on the skywalk].

Hong Kong: Dung Kai-cheung 董啟章. Ditu ji 地圖集 [Atlas] and Dorothy Tse 謝曉虹. Shuang cheng cidian I–II 雙城 辭典I–II [A dictionary of two cities I–II] (written jointly with Hon Lai Chu).

The CORPUS of the book is then dedicated to the study of the countless fictional cities nestled within the six literary works written by authors from the 3 real-world metropoles Hong Kong, Taipei, and Shanghai. In the following readings, “I turn my attention away from each real-world city as a center of gravity and toward the analytical interactions between these three bodies of equal mass. For the sake of intelligibility, and to foster such interactions, I impose a theoretical and thematic framework characterized by a high degree of flexibility.”

Part I. Skeleton

Chapter 1. Literary Sensory Studies: The Body Remembers the City

Chapter 2. The Three-City Problem: A Kaleidoscope of Six Works

Part II. Corpus

Chapter 3. Sense of Place: Walking or Mapping the City Chapter

4. The Nose: Flora Nostalgia Chapter

5. The Ear: Melody of Language Chapter

6. Sense of Self: The Many Skins of the City Chapter

7. The Mouth: Balancing Flavors Chapter

8. The Eye: Fictional Dreams

Part III. Excretions

Chapter 9. Sense of Time: Everyday Rhythms

The City Remembers: Concluding Remarks

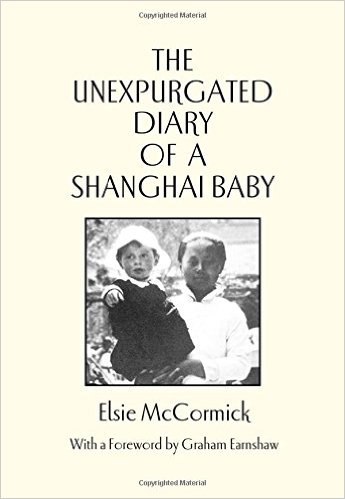

In the satirical tidbits of American journalist Elsie McCormick’s The Unexpurgated Diary of a Shanghai Baby from 1927, we see the ‘Paris of the Orient’ through the eyes of an American toddler. Most of the baby’s revealing observations satirize the foreign settlers’ ignorance of everything beyond their own small social sphere (including the everyday life of their own child). The baby itself has an even more limited social life: Apart from its amah, its only social intercourse is a distance aquantainship with a Japanese baby – perambulators that pass in the night… One might compare the baby’s mix of awe and resentment towards the ‘fresh Jap baby’ to the American attitude to the growing Japanese militarism of the time:

In the satirical tidbits of American journalist Elsie McCormick’s The Unexpurgated Diary of a Shanghai Baby from 1927, we see the ‘Paris of the Orient’ through the eyes of an American toddler. Most of the baby’s revealing observations satirize the foreign settlers’ ignorance of everything beyond their own small social sphere (including the everyday life of their own child). The baby itself has an even more limited social life: Apart from its amah, its only social intercourse is a distance aquantainship with a Japanese baby – perambulators that pass in the night… One might compare the baby’s mix of awe and resentment towards the ‘fresh Jap baby’ to the American attitude to the growing Japanese militarism of the time: Seen through the eyes of its (fictional) younger inhabitants, the international community of 1920s’ Shanghai reveals itself to be not so much decadent and cosmopolitan as suffering from ineffectual self isolation and quite a lot of prudish village atmosphere. If the settlement was itself a little ethnically confused (witness the municipal flag), the important part was that it was not Chinese. The arbitrariness and impotence of these lines drawn in the sand become humourously apparent when narrated from a child’s perspective. After reading quite a lot of literary descriptions of Shanghai as “the adventurers’ paradise” towards the undoing of all good men and women, it is quite liberating to see that image messed up a bit.

Seen through the eyes of its (fictional) younger inhabitants, the international community of 1920s’ Shanghai reveals itself to be not so much decadent and cosmopolitan as suffering from ineffectual self isolation and quite a lot of prudish village atmosphere. If the settlement was itself a little ethnically confused (witness the municipal flag), the important part was that it was not Chinese. The arbitrariness and impotence of these lines drawn in the sand become humourously apparent when narrated from a child’s perspective. After reading quite a lot of literary descriptions of Shanghai as “the adventurers’ paradise” towards the undoing of all good men and women, it is quite liberating to see that image messed up a bit.

“With a number of twists and turns, the tram skirts Victoria Park and the Tin Hau Temple (one of Hong Kong’s oldest) on its way to North Point, Quarry Bay, and Shau Kei Wan at the eastern tip of the island. The ride is convenient, if not comfortable, and the panorama of buildings and people moving by in slow motion gives one the feeling of travelling backward through time – a nostalgic antidote for the stomach-churning, competitive pace of Central Business District.”

“With a number of twists and turns, the tram skirts Victoria Park and the Tin Hau Temple (one of Hong Kong’s oldest) on its way to North Point, Quarry Bay, and Shau Kei Wan at the eastern tip of the island. The ride is convenient, if not comfortable, and the panorama of buildings and people moving by in slow motion gives one the feeling of travelling backward through time – a nostalgic antidote for the stomach-churning, competitive pace of Central Business District.”

In Midnight the head of the Wu family, a pious country gentleman, expires on his very first day in Shanghai from sheer shock of its depravity. The city itself seems to him monstrous, while at the same time curiously ephemeral, and intent upon wrecking moral havoc on all who enter: “Good heavens! the towering skyscrapers, their countless lighted windows gleaming like eyes of devils, seemed to be rushing down on him like an avalanche at one moment and vanishing the next.” (15)

In Midnight the head of the Wu family, a pious country gentleman, expires on his very first day in Shanghai from sheer shock of its depravity. The city itself seems to him monstrous, while at the same time curiously ephemeral, and intent upon wrecking moral havoc on all who enter: “Good heavens! the towering skyscrapers, their countless lighted windows gleaming like eyes of devils, seemed to be rushing down on him like an avalanche at one moment and vanishing the next.” (15) Signifying the quick demise of old traditions and values in the new world of the 1930s, with its unpredictable civil war and its extreme financial instability, the scene is set for a dramatization of a historical changes in China. The natural stage for such a scene is Shanghai, enabling professor Yu-ting, when a young lady asks him to describe contemporary society, to answer:

Signifying the quick demise of old traditions and values in the new world of the 1930s, with its unpredictable civil war and its extreme financial instability, the scene is set for a dramatization of a historical changes in China. The natural stage for such a scene is Shanghai, enabling professor Yu-ting, when a young lady asks him to describe contemporary society, to answer: The dead man in Chen Danyan’s story (though true to a certain type of character in recent Shanghai history, being a dispossessed factory owner with children educated abroad) is more important for the sense of emotional loss his death induces. The loss of one personal version of the past.

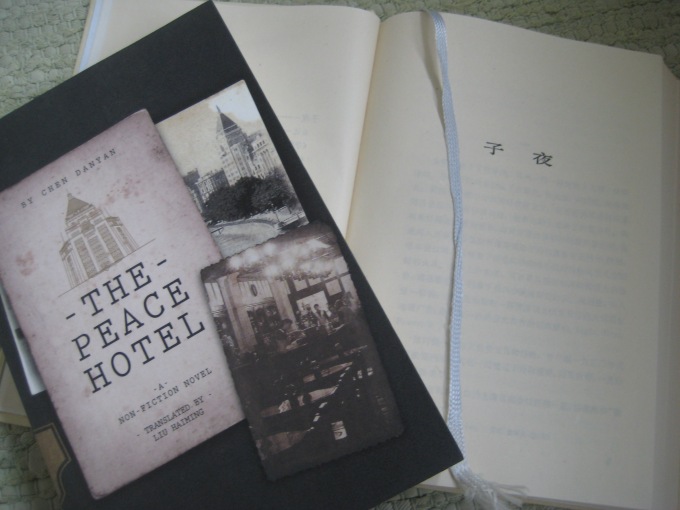

The dead man in Chen Danyan’s story (though true to a certain type of character in recent Shanghai history, being a dispossessed factory owner with children educated abroad) is more important for the sense of emotional loss his death induces. The loss of one personal version of the past. Chen Danyan’s somewhat eclectic “non-fiction novel” is a testament to the plurality of personal and emotional ties to the Shanghai of yore as well as to one of its most spectacular iconic spaces, the Peace Hotel: “Regret for it’s being ‘unlike how it was in the past’ welled up inside me, yet, interestingly; I found it hard to pin down the ‘past.’ The people I had interviewed and I myself couldn’t help talking about the hotel’s past, which often meant our respective first encounter with it.” (252)

Chen Danyan’s somewhat eclectic “non-fiction novel” is a testament to the plurality of personal and emotional ties to the Shanghai of yore as well as to one of its most spectacular iconic spaces, the Peace Hotel: “Regret for it’s being ‘unlike how it was in the past’ welled up inside me, yet, interestingly; I found it hard to pin down the ‘past.’ The people I had interviewed and I myself couldn’t help talking about the hotel’s past, which often meant our respective first encounter with it.” (252)