小说 planetary xiaoshuo 小說

This blog is devoted to critical monster plants, literary senses, spacetime narratology, queering translation, and speculative Sinophone fiction from across the globe.

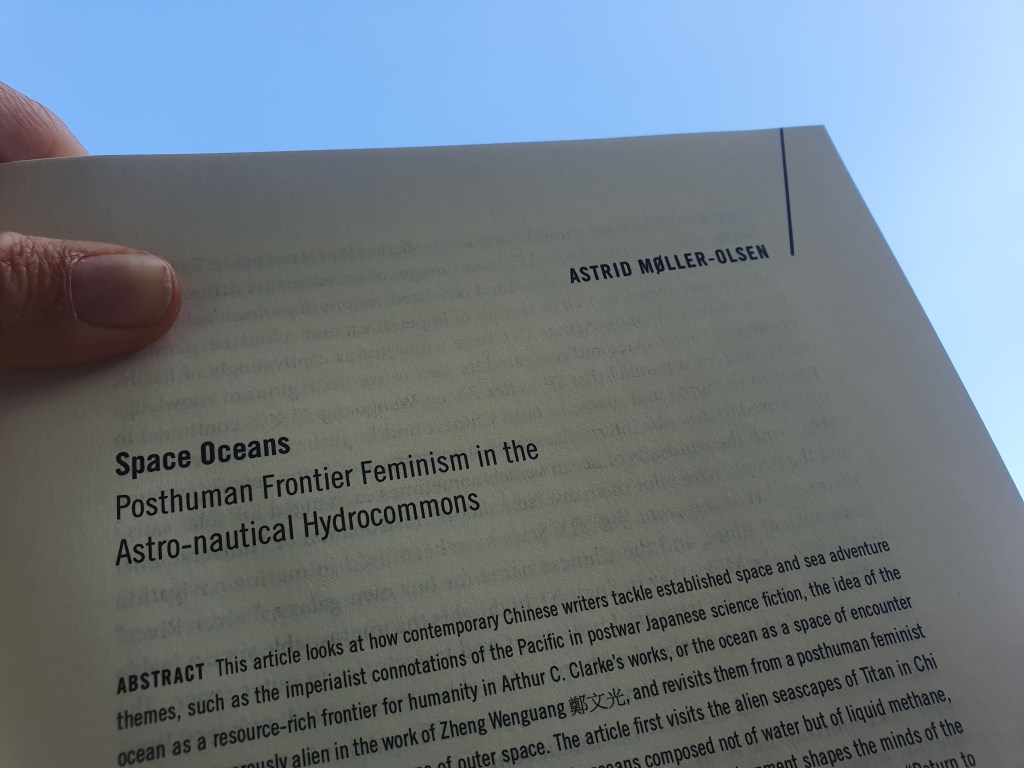

By Dr. Astrid Møller-Olsen, translator & literary scholar, University of Copenhagen

ACCL alcohol Can Xue Chinese fiction Chi Ta-wei comparative literature crime fiction critical plant studies Daoism eating ecocriticism feminism fictional dictionaries gender Han Shaogong Hong Kong libraries literary plants literary sensory studies literary theory Lu Xun memory monster plants Mo Yan nostalgia plants poetry queer reading science fiction sensory studies Shanghai Sinophone fiction spacetime Speculative Fiction Taipei Taiwan Taiwanese literature translation trees Urban Fiction urban memory Yu Hua Zhong Acheng Zhuangzi